Note: This article heavily refers back to topics discussed in episode 38 of “The Veef Show” podcast. Also, please read “The Imai Files” by Roger Harkavy for information on their role in the creation of Genesis Climber Mospeada and Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross.

The lasting legacy of Super Dimension Fortress Macross is easily observable in Japanese pop culture. Examples of dynamic action, idol singers, and anime-fans-turned-anime-producers are so ubiquitous that Macross could be considered a vital part of anime’s “DNA.” However, the show’s immediate impact on the media landscape of the 1980s is not as well understood. Like many merchandise-driven anime of its era, Macross was pitched to a variety of sponsors who worked with the show’s staff (creator/mechanical designer Shoji Kawamori in particular), to create a series that could be successfully marketed as physical goods. As typical of a Robot Anime, the sponsors mainly focused on representations of the show’s various mecha, with Takatoku handling the toys and a tag-team of Imai and Arii producing plastic model kits. These three companies would continue to sponsor and heavily influence the shows that followed in Macross’s wake.

Advertisement for books featuring the products of Imai and Arii. Note both Macross and Orguss are shown.

While it is true that Macross’s success afforded it a lavish movie adaptation in the form of “Do You Remember Love?”, the sponsors supporting the series were already gearing up for the next series with Super Dimension Century Orguss. Merchandise-driven shows (Robot Anime especially) were expected to last a year, with episode counts in the 26-39 range (two to three “Cours”) with direct sequels (i.e. Mazinger Z to Great Mazinger) being uncommon. As such, Orguss was groomed to be a follow up much in the same vein as Macross with many of the same creative forces involved (animation production by Artland and mechanical designs by Kazutaka Miyatake of Studio Nue).

Boxes for Macross and Orguss model kits by Arii. Note how both feature similar artwork, layout, and styling to maintain a clear sense of branding. In addition, the term “Gerwalk” and the practice of ending the design’s robot mode’s name with “-oid” carried over from Macross to Orguss.

The same can be said for Macross and Orguss toys by Takatoku.

Takatoku’s 1/55 scale VF-1 Valkyrie is often cited as the quintessential transformable robot toy, with the figure’s large production run (over a million sold in the 1980s) and numerous re-issues by Bandai being signs of its success. However, the toy’s complexity and size meant it was sold on thin profit margins with Takatoku making relatively little money compared to the cost of manufacturing. When the company moved to making Orguss products, the show’s more unconventional mechanical designs proved difficult to adapt into toys with contemporary 1980s toy technology. As a result, Orguss toys often broke in package. In addition, Takatoku’s attempts to expand their toy line to include more secondary and enemy mecha backfired as the figures for the M.Lover craft and Chiram Gerwalks were especially fragile. To this day, finding examples of those toys intact (either loose or mint in package) is extremely difficult.

As Orguss was winding down, Takatoku and Imai/Arii experienced somewhat of a “split”, with the companies lending their support to competing Robot Anime produced without any involvement from Macross or Orguss staff. These shows, Special Armored Battalion Dorvack (Ashi Productions/Production Reed) and Genesis Climber Mospeada (Tatsunoko with designs by Artmic), borrowed heavily from Macross in a way that was probably encouraged by the sponsors. Takatoku handled the toy side of Dorvack, while Mospeada’s figures were produced under Gakken. The latter is notable for being a book publishing company that had briefly entered (and quickly exited) the robot toy arena during the trend’s heyday in the 80s.

Dorvack and Mospeada debuted within weeks of each other in October 1983. Takatoku’s style and branding remained consistent since Macross. Gakken would imitate their competitor’s style.

In many ways, the simple and robust designs of the Variable Vehicle from Dorvack were a direct response to the unconventional and complex designs of Orguss. Takatoku even went as far as to omit anything on the large-sized transformable figures that was not essential to converting between modes. As such, the Mugen Calibur, Ovelon Gazzette, and Bonaparte Tulcas lacked features like working elbows, knees, and even shoulder joints with more than one axis of movement. The Dorvack toy line itself also focused almost exclusively on the three main Variable Vehicles, with the trio being offered in various sizes both with and without the ability to transform. And while a pair of Powered Armor toys representing the show’s secondary mecha were produced, none of the enemy Idelian craft were produced.

Gakken’s Mospeada product line was similarly limited, with focus being the Legioss transformable airplane and the titular Mospeada Ride Armors. Both the Legioss and Rider Armor were offered in several sizes with varying levels of transformability. A small sized toy of the Legioss’s partner mecha, the TREAD, was released in extremely limited numbers in Japan (though more were released by a distributor called “Lansay” in France). And like with Takatoku’s handling of Dorvack, Gakken produced no toys of the enemy mecha.

Model kits for Dorvack were produced by Gunze Sangyo while Imai (along with a company called “LS”) handled Mospeada. Again, it was Imai’s style that remained consistent since the Macross era, with their competitor following suit.

In sharp contrast to Takatoku’s limited toy offerings, Gunze Sangyo produced a wide selection of Dorvack’s secondary and enemy mecha. This approach mimics what Imai and Arii had done a year prior with their Macross and Orguss kits.

Gunze Sangyo even moved beyond what was shown in the series with variations of Dorvack’s Variable Vehicles and Powered Suits filling out the ranks of the model kits. Imai and LS would not be as ambitious with their competing Mospeada kits, with only the Legioss and two main Ride Armor types being represented. A kit of the TREAD was planned but never released. No enemy mecha kits were released by either Imai or LS.

Page 99 of Roger Harkavy’s Imai Files features a photograph of Mospeada’s production and an important note about the necessity of sponsors and a Robot Anime’s production:

“List of 39 episodes scheduled for production, complete with air dates and animation studios

assigned to each. Unfortunately MOSPEADA was halted at the 25 episode mark due to low interest in the show and associated merchandise. ”

Around 1984, Takatoku suffered several financial setbacks with neither Orguss nor Dorvack achieving the same level of success as Macross. Bandai would end up acquiring the tooling and production rights to Takatoku’s large Macross and Dorvack toys, with examples from both shows being integrated into Hasbro’s up and coming Transformers toy line (Jetfire and Deluxe Autobots Roadbuster and Whirl).

Around this time, a short-lived Robot Anime called Chou Kousoku Galvion, existed as another venue for Imai, Arii, and LS to sell their model kits.

Galvion kits ranged from the titular transformable car, to secondary mecha, and enemy Metal Battlers.

The main sponsor of the show is rumored to have been Takatoku, who by 1984 were in a sharp decline due to diminishing returns on both Orguss and Dorvack. However, some Galvion toys did make it to retailers, just without the name. A large transformable Galvion with all the earmarks of Takatoku was sold in unmarked clear plastic bag with a manufacturer’s stamp saying it was produced by TYCO (you can read more about here ). Small transformable toys of the Galvion, Zector, and two enemy vehicles were released with modified head designs as “Super ROBO Car”series by a company called Mark (マーク). You can find pictures for the Indy figure (Galvion) with packaging photos here). These same figures would be distributed in North America under the “Converters” brand by another company called Select. Since Select also released several Macross, Orguss, and Dorvack figures as Converters, Mark was probably the sub-contractor that produced the small-scale toys for Takatoku and was simply recouping costs on unused Galvion toy molds.

Book excerpt speculating on the transformable Galvion’s unclear origins.

Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross would be the last entry in the loosely connected “Super Dimension” trilogy. The biggest links between Macross, Orguss, and Southern Cross were: financial backing by advertising firm, Big West, a 2:00 PM timeslot on Sundays, and the presence of Imai and Arii handling the model kit side of the merchandise. On the production end, Southern Cross was animated entirely by Tatsunoko with mechanical designs by their in-house studio, “Ammonite.” Bandai, not Takatoku, is rumored to have had the toy merchandising rights to the series (possibly acquired along with the Macross and Dorvack rights from a dying Takatoku), but no action figures were produced for the show in its native Japan. In essence, the “Super Dimension” title was more a kind of branding, under which one could infer the shows would have a similar, look, feel, and most importantly: merchandise.

Since the TV broadcasts for Galvion and Southern Cross overlapped, model kit catalogs would feature product from both series.

The model kits for Super Dimension Southern Cross focused mostly on the “Arming Doublet” armor used by the main characters. The only vehicle kit produced was the Flash Clapper hover cycle. Likewise, only one mecha kit made it to retail in the form of the enemy Sol Bioroid.

Imai catalog showing more Arming Doublet kits as well as plans for a 1/48 scale Spartas hover tank. The latter was cancelled.

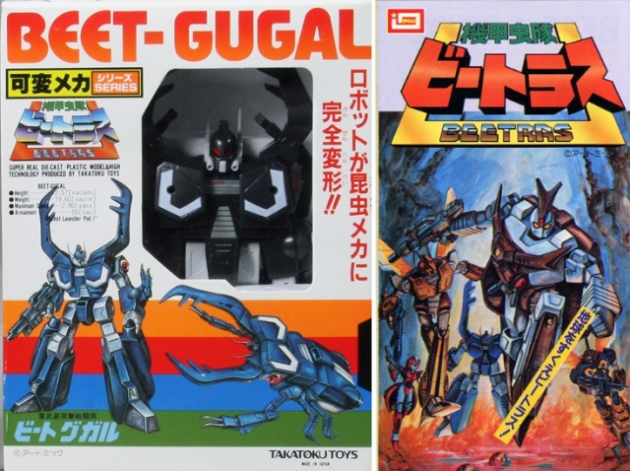

The final collaboration between Takatoku Toys and Imai was an obscure transformable robot line called Armored Insect Corps Beetras. While it featured designs by studio Artmic, there was no supporting anime produced. The toy molds were sold to Bandai with the same deal that landed them Macross and Dorvack figures. Like with those two properties, the Beetras toys would be repurposed as Transformers.

Newtype Magazine article marking the arrival of the Transformers animated series in Japan. Takara, who produced the original “Diaclone” and “Microchange” toys Hasbro licensed to create the Transformers, relaunched their toys to reflect this new property.

(Newtype Magazine Article scan from Oldtype/Newtype.)

By 1985, Takatoku Toys had effectively gone out of business with many of its assests sold to other toy companies. Likewise, Imai had sold many of their Macross kit molds and tooling to rival company, Bandai (with some of these assests being only recently rediscovered within the past decade). This was also the year that Transformers was launched in Japan, and would not leave airwaves or shelves until around 1992. In addition, the OVA market exploded onto the scene with many of the young talent involved in making the shows Takatoku and Imai had sponsored moving on to producing direct-to-video anime aimed at an older audience. Moreover, those renting and/or buying up all these extravagant home videos were the very same children that grew up watching Macross, its follow-ups, and imitators.

A year later, Sunrise and Bandai started the big Gundam revival with the first sequel series, Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam. It should be noted that the titular robots in Zeta Gundam and its own sequel, ZZ Gundam, were both transformable mecha with a kind of airplane alternative mode. In a sense, the things that made Macross unique had already diffused into the greater anime creative sphere with many of its visual motifs like missile swarms, high-speed action, and transforming robots becoming common place in Japanese pop culture. For sponsors like Takatoku and Imai, attempting to replicate the success of Macross’s specific brand of Real Robot Anime mixed with merchandise-friendly variable machines and exotic enemy mecha proved to be disastrous for them in a very short amount of time. It would be Transformers and other kid-oriented product lines such as Machine Robo, that replaced Macross-type shows entirely. Perhaps the last series in that vein would be Red Photon Zillion, a show by Tatsunoko Productions, that featured a transformable three-wheeled bike. However, the main sponsor of that series was Sega, who mostly focused on the associated laser tag toy and video games for their new Mark III/Master System console. It is often said the original Super Dimension Fortress Macross demonstrated the “Anime Generation’s” ability to take everything they had loved and learned from the shows of the 60’s and 70’s and take the medium to another level. With that in mind, one must not forget that Japanese animation is a heavily commercialized form of art, and the way that art shaped the world of its associated merchandise is an important part of Macross’s legacy.

Special thanks to fellow CollectionDX writer Leonardo Flores, Richard Clark of the Gubabablog, and Japanese pop culture researcher and member of the Macross Speaker Podcast: Renato Rivera Rusca for helping make this article possible.

Images used in this article are for illustrative purposes only and are property of their original owners.